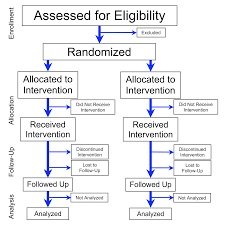

Quasi-experiments are a lot of work, yet don’t have the same scientific power to show cause and effect, as do randomized controlled trials (RCTs). An RCT would provide better support for any hypothesis that X causes Y. [As a quick review of what quasi-experimental versus RCT studies are, see “Of Mice & Cheese” and/or “Out of Control (Groups).”]

Quasi-experiments are a lot of work, yet don’t have the same scientific power to show cause and effect, as do randomized controlled trials (RCTs). An RCT would provide better support for any hypothesis that X causes Y. [As a quick review of what quasi-experimental versus RCT studies are, see “Of Mice & Cheese” and/or “Out of Control (Groups).”]

So why do quasi-experimental studies at all? Why not always do RCTs when we are testing cause and effect? Here are 3 reasons:

#1 Sometimes ETHICALLY the researcher canNOT randomly assign subjects to a control  and an experimental group. If the researcher wants to compare health outcomes of smokers with non-smokers, the researcher cannot assign some people to smoke and others not to smoke! Why? Because we already know that smoking has significant harmful effects. (Of course, in a dictatorship, by using the police a researcher could assign them to smoke or not smoke, but I don’t think we wanna go there.)

and an experimental group. If the researcher wants to compare health outcomes of smokers with non-smokers, the researcher cannot assign some people to smoke and others not to smoke! Why? Because we already know that smoking has significant harmful effects. (Of course, in a dictatorship, by using the police a researcher could assign them to smoke or not smoke, but I don’t think we wanna go there.)

#2 Sometimes PHYSICALLY the researcher canNOT randomly assign subjects to control &  experimental groups. If the researcher wants to compare health outcomes of

experimental groups. If the researcher wants to compare health outcomes of

individuals from different countries, it is physically impossible to assign country of origin.

#3 Sometimes FINANCIALLY the researcher canNOT afford to assign subjects randomly  to control & experimental groups. It costs $ & time to get a list of subjects and then assign them to control & experimental groups using random numbers table or drawing names from a hat.

to control & experimental groups. It costs $ & time to get a list of subjects and then assign them to control & experimental groups using random numbers table or drawing names from a hat.

Thus, researchers sometimes are left with little alternative, but to do a quasi-experiment as the next best thing to an RCT, then discuss its limitations in research reports.

Critical Thinking: You read a research study in which a researcher recruits the 1st 100 patients on a surgical ward January-March quarter as a control group. Then the researcher recruits the 2nd 100 patients on that same surgical ward April-June for the experimental group. With the experimental group, the staff uses a new, standardized pain script for better pain communications. Then the pain communication outcomes of each group are compared statistically.

- Is this a quasi-experiment or a randomized controlled trial (RCT)?

- What factors (variables) might be the same among control & experimental groups in this study?

- What factors (variables) might be different between control & experimental groups that might affect study outcomes?

- How could you design an ethical & possible RCT that would overcome the problems with this study?

- Why might you choose to do the study the same way that this researcher did?

For more info: see “Of Mice & Cheese” and/or “Out of Control (Groups).”

![welcome[1]](https://discoveringyourinnerscientist.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/welcome1.gif?w=163&h=119)

Herein lies a weak link in the cause-and-effect chain. Quasi- designs are NOT as strong as true experimental designs because something other than our treatment (in this case pet therapy) may have created any difference in outcomes (e.g., anxiety levels). Why? Here’s your answer.

Herein lies a weak link in the cause-and-effect chain. Quasi- designs are NOT as strong as true experimental designs because something other than our treatment (in this case pet therapy) may have created any difference in outcomes (e.g., anxiety levels). Why? Here’s your answer.

In a quasi experimental design

In a quasi experimental design

will know the technical things you need to plan into your study in order to make the study ‘sparkle’ and to get approval from human subjects review committees. The person doesn’t have to be an expert on your topic. You fill that role, or soon will!

will know the technical things you need to plan into your study in order to make the study ‘sparkle’ and to get approval from human subjects review committees. The person doesn’t have to be an expert on your topic. You fill that role, or soon will! librarians are worth their weight in gold! Librarians can help you find what others have learned about your topic already, and then you can build on that knowledge. [note: check out

librarians are worth their weight in gold! Librarians can help you find what others have learned about your topic already, and then you can build on that knowledge. [note: check out  This will help you to establish whether or not there really is a problem to be solved. Descriptive studies are much simpler to conduct and analyze than experimental studies in which you measure something, make an improvement, and then see if the improvement improved things. For example, you would measure sleep interruptions, institute a quiet time, and then measure sleep interruptions again to see if there were fewer. [check out

This will help you to establish whether or not there really is a problem to be solved. Descriptive studies are much simpler to conduct and analyze than experimental studies in which you measure something, make an improvement, and then see if the improvement improved things. For example, you would measure sleep interruptions, institute a quiet time, and then measure sleep interruptions again to see if there were fewer. [check out  Every researcher from time to time can feel ‘bogged down’ or bored with what they are doing, & one of the best protections against that is making sure you think the topic is super-interesting in the first place. If you get a little bored or stuck later don’t be surprised; it just means you’re pretty normal. Those stuck times might even feel like “hitting the wall” in a long race, and once you get past it things get better. Remind yourself why you loved the topic in the first place. Talk to your PhD friend or a mentor for encouragement. Take a little break. Read something really interesting about your topic.

Every researcher from time to time can feel ‘bogged down’ or bored with what they are doing, & one of the best protections against that is making sure you think the topic is super-interesting in the first place. If you get a little bored or stuck later don’t be surprised; it just means you’re pretty normal. Those stuck times might even feel like “hitting the wall” in a long race, and once you get past it things get better. Remind yourself why you loved the topic in the first place. Talk to your PhD friend or a mentor for encouragement. Take a little break. Read something really interesting about your topic.

KEY POINTS:

KEY POINTS: no, the response tells us only how the patient remembers it.

no, the response tells us only how the patient remembers it. see

see  (

(

measures

measures

Is pain experience as diverse as our populations? This week I came across an interesting meta-analysis.

Is pain experience as diverse as our populations? This week I came across an interesting meta-analysis. (RCTs) or experimental studies is the strongest type of MA. MA based on descriptive or non-experimental studies is a little less strong, because it just describes things as they seem to be; & it cannot show that one thing causes another.

(RCTs) or experimental studies is the strongest type of MA. MA based on descriptive or non-experimental studies is a little less strong, because it just describes things as they seem to be; & it cannot show that one thing causes another.

your practice? Or should it? How can you use the findings with your patients? Should each patient be treated as a completely unique individual? Or what are the pros & cons of using this MA to give us a starting point with groups of patients? [To dialogue about this, comment below.]

your practice? Or should it? How can you use the findings with your patients? Should each patient be treated as a completely unique individual? Or what are the pros & cons of using this MA to give us a starting point with groups of patients? [To dialogue about this, comment below.] library using reference above. It is available electronically pre-publication. Also check out my

library using reference above. It is available electronically pre-publication. Also check out my