A research design is the investigator-chosen, overarching study framework that facilitates getting the most accurate answer to a hypothesis or question. Think of research design as similar to the framing of a house during construction. Just as house-framing provides structure and limits to walls, floors, and ceilings, so does a research design provide structure and limits to a host of protocol details.

| Tip. The two major categories of research design are: 1) Non-experimental, observation only and 2) Experimental testing of an intervention. |

DESCRIPTIVE STUDIES

Non-experimental studies that examine one variable at a time.

When little is known and no theory exists on a topic, descriptive research begins to build theory by identifying and defining key, related concepts (variables). Although a descriptive study may explore several variables, only one of those is measured at a time; there is no examination of relationships between variables. Descriptive studies create a picture of what exists by analyzing quantitative or qualitative

data to answer questions like, “What is [variable x]?” or “How often does it occur?” Examples of such one-variable questions are “What are the experiences of first-time fathers?” or “How many falls occur in the emergency room?” (Variables are in italics.) The former question produces qualitative data, and the latter, quantitative.

Descriptive results raise important questions for further study, and findings are rarely generalizable. You can see this especially in a descriptive case study: an in-depth exploration of a single event or phenomena that is limited to a particular time and place. Given case study limitations, opinions differ on whether they even qualify as research.

Descriptive research that arises from constructivist or advocacy assumptions merits particular attention. In these designs, researchers collect in-depth qualitative information about only one variable and then critically reflect on that data in order to uncover emerging themes or theories. Often broad data are collected in a natural setting in which researchers exercise little control over other variables. Sample size is not pre-determined, data collection and analysis are concurrent, and the researcher collects and analyzes data until no new ideas emerge (data saturation). The most basic qualitative descriptive method is perhaps content analysis, sometimes called narrative descriptive analysis, in which researchers uncover themes within informant descriptions. Figure 4 identifies major qualitative traditions beyond content analysis and case studies.

| Alert! All qualitative studies are descriptive, but not all descriptive studies are qualitative. |

Box 1. Descriptive Qualitative Designs

| Design | Focus | Discipline of Origin |

| Ethnography | Uncovers phenomena within a given culture, such as meanings, communications, and mores. | Anthropology |

| Grounded Theory | Identifies a basic social problem and the process that participants use to confront it. | Sociology |

| Phenomenology | Documents the “lived experience” of informants going through a particular event or situation. | Psychology |

| Community participatory action | Seeks positive social change and empowerment of an oppressed community by engaging them in every step of the research process. | Marxist political theory |

| Feminist | Seeks positive social change and empowerment of women as an oppressed group. | Marxist political theory |

Predatory journals don’t meet quality peer-review standards.

Predatory journals don’t meet quality peer-review standards. Stay safe. As Randy Newman sings,

Stay safe. As Randy Newman sings,

One source of rich word or narrative (qualitative) data for answering nursing questions is nurses’ stories. Dr. Pat Benner RN, author of Novice to Expert explains two things we can do to help nurses fully tell their stories so we can learn the most from their practice.

One source of rich word or narrative (qualitative) data for answering nursing questions is nurses’ stories. Dr. Pat Benner RN, author of Novice to Expert explains two things we can do to help nurses fully tell their stories so we can learn the most from their practice.

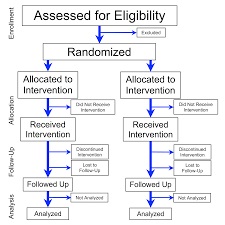

Quasi-experiments are a lot of work, yet don’t have the same scientific power to show cause and effect, as do randomized controlled trials (RCTs). An RCT would provide better support for any hypothesis that X causes Y. [As a quick review of what quasi-experimental versus RCT studies are, see

Quasi-experiments are a lot of work, yet don’t have the same scientific power to show cause and effect, as do randomized controlled trials (RCTs). An RCT would provide better support for any hypothesis that X causes Y. [As a quick review of what quasi-experimental versus RCT studies are, see  and an experimental group. If the researcher wants to compare health outcomes of smokers with non-smokers, the researcher cannot assign some people to smoke and others not to smoke! Why? Because we already know that smoking has significant harmful effects. (Of course, in a dictatorship, by using the police a researcher could assign them to smoke or not smoke, but I don’t think we wanna go there.)

and an experimental group. If the researcher wants to compare health outcomes of smokers with non-smokers, the researcher cannot assign some people to smoke and others not to smoke! Why? Because we already know that smoking has significant harmful effects. (Of course, in a dictatorship, by using the police a researcher could assign them to smoke or not smoke, but I don’t think we wanna go there.) experimental groups. If the researcher wants to compare health outcomes of

experimental groups. If the researcher wants to compare health outcomes of to control & experimental groups. It costs $ & time to get a list of subjects and then assign them to control & experimental groups using random numbers table or drawing names from a hat.

to control & experimental groups. It costs $ & time to get a list of subjects and then assign them to control & experimental groups using random numbers table or drawing names from a hat.

In a quasi experimental design

In a quasi experimental design

will know the technical things you need to plan into your study in order to make the study ‘sparkle’ and to get approval from human subjects review committees. The person doesn’t have to be an expert on your topic. You fill that role, or soon will!

will know the technical things you need to plan into your study in order to make the study ‘sparkle’ and to get approval from human subjects review committees. The person doesn’t have to be an expert on your topic. You fill that role, or soon will! librarians are worth their weight in gold! Librarians can help you find what others have learned about your topic already, and then you can build on that knowledge. [note: check out

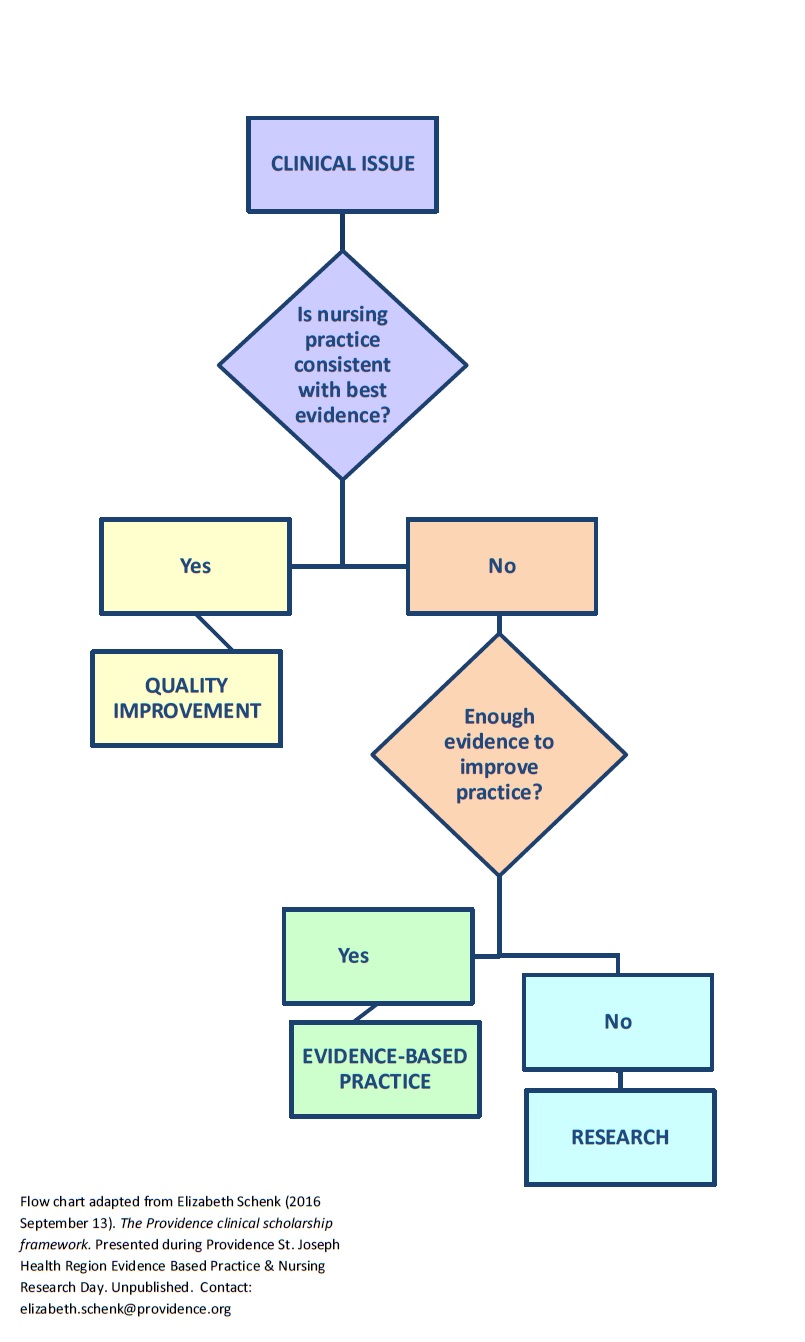

librarians are worth their weight in gold! Librarians can help you find what others have learned about your topic already, and then you can build on that knowledge. [note: check out  This will help you to establish whether or not there really is a problem to be solved. Descriptive studies are much simpler to conduct and analyze than experimental studies in which you measure something, make an improvement, and then see if the improvement improved things. For example, you would measure sleep interruptions, institute a quiet time, and then measure sleep interruptions again to see if there were fewer. [check out

This will help you to establish whether or not there really is a problem to be solved. Descriptive studies are much simpler to conduct and analyze than experimental studies in which you measure something, make an improvement, and then see if the improvement improved things. For example, you would measure sleep interruptions, institute a quiet time, and then measure sleep interruptions again to see if there were fewer. [check out  Every researcher from time to time can feel ‘bogged down’ or bored with what they are doing, & one of the best protections against that is making sure you think the topic is super-interesting in the first place. If you get a little bored or stuck later don’t be surprised; it just means you’re pretty normal. Those stuck times might even feel like “hitting the wall” in a long race, and once you get past it things get better. Remind yourself why you loved the topic in the first place. Talk to your PhD friend or a mentor for encouragement. Take a little break. Read something really interesting about your topic.

Every researcher from time to time can feel ‘bogged down’ or bored with what they are doing, & one of the best protections against that is making sure you think the topic is super-interesting in the first place. If you get a little bored or stuck later don’t be surprised; it just means you’re pretty normal. Those stuck times might even feel like “hitting the wall” in a long race, and once you get past it things get better. Remind yourself why you loved the topic in the first place. Talk to your PhD friend or a mentor for encouragement. Take a little break. Read something really interesting about your topic.