The difference between research and evidence-based practice (EBP) can sometimes be confusing, but the contrast between them is sharp. I think most of the confusion comes because those implementing both processes measure outcomes. Here are differences:

- RESEARCH : The process of research (formulating an answerable question, designing project methods, collecting and analyzing the data, and interpreting the

meaning of results) is creating knowledge (AKA creating research evidence). A research project that has been written up IS evidence that can be used in practice. The process of research is guided by the scientific method.

meaning of results) is creating knowledge (AKA creating research evidence). A research project that has been written up IS evidence that can be used in practice. The process of research is guided by the scientific method. - EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE: EBP is using existing knowledge (AKA using

research evidence) in practice. While researchers create new knowledge,

research evidence) in practice. While researchers create new knowledge,

The creation of evidence obviously precedes its application to practice. Something must be made before it can be used. Research obviously precedes the application of research findings to practice. When those findings are applied to practice, then we say the practice is evidence-based.

A good analogy for how research & EBP differ & work together can be seen in autos.

- Designers & factory workers create new cars.

Using a car! - Drivers use existing cars that they choose according to preferences and best judgments about safety.

CRITICAL THINKING: 1) Why is the common phrase “evidence-based research” unclear? Should you use it? Why or why not? 2) What is a clinical question you now face. (e.g., C.Diff spread; nurse morale on your unit; managing neuropathic pain) and think about how the Stetler EBP model at http://www.nccmt.ca/registry/resource/pdf/83.pdf might help. Because you will be measuring outcomes, then why is this still considered EBP.

Go to full article

Go to full article during Christmas 2015. This was correlated with rates of absenteeism from primary school, conviction rates in young people (aged 10-17 years), distance from hospital to North Pole (closest city or town to the hospital in kilometres, as the reindeer flies), and contextual socioeconomic deprivation (index of multiple deprivation).

during Christmas 2015. This was correlated with rates of absenteeism from primary school, conviction rates in young people (aged 10-17 years), distance from hospital to North Pole (closest city or town to the hospital in kilometres, as the reindeer flies), and contextual socioeconomic deprivation (index of multiple deprivation). Is it quantitative or qualitative research? Experimental or non-experimental research? How generalizable is this research? What are the risks,resources, and readiness of people in potentially using the findings (Stetler & Marram, 1996; Stetler, 2001)? What might happen if you try to apply the abstract information to practice without reading the full article? Do you think the project done in Europe is readily applicable to America? What would be the next level of research that you might undertake to better confirm these findings?

Is it quantitative or qualitative research? Experimental or non-experimental research? How generalizable is this research? What are the risks,resources, and readiness of people in potentially using the findings (Stetler & Marram, 1996; Stetler, 2001)? What might happen if you try to apply the abstract information to practice without reading the full article? Do you think the project done in Europe is readily applicable to America? What would be the next level of research that you might undertake to better confirm these findings?

research. My key point? Much so-called “unfiltered research” has been screened (filtered) carefully through peer-review before publication; while some “filtered research” may have been ‘filtered’ only by a single expert & be out of date. If we use the terms filtered and unfiltered we should not be naive about their meanings. (Pyramid source:

research. My key point? Much so-called “unfiltered research” has been screened (filtered) carefully through peer-review before publication; while some “filtered research” may have been ‘filtered’ only by a single expert & be out of date. If we use the terms filtered and unfiltered we should not be naive about their meanings. (Pyramid source:  You may have heard of Benner’s Novice to Expert theory. Benner used in-depth, qualitative interview descriptions as data to generate her theory. Yet that type of research evidence is missing from medicine’s pyramid! Without a clear foundation the pyramid will just topple over. Better be clear!

You may have heard of Benner’s Novice to Expert theory. Benner used in-depth, qualitative interview descriptions as data to generate her theory. Yet that type of research evidence is missing from medicine’s pyramid! Without a clear foundation the pyramid will just topple over. Better be clear!

Abstracts can mislead

Abstracts can mislead  encourage us, Don’t give up reading the full article just because some parts of the study may be hard to understand. Just read and get what you can, then re-read the difficult-to-understand parts. Get some help with those PRN.

encourage us, Don’t give up reading the full article just because some parts of the study may be hard to understand. Just read and get what you can, then re-read the difficult-to-understand parts. Get some help with those PRN.

“Once you see Nightingale’s graph, the terrible picture is clear. The Russians were a minor enemy. The real enemies were cholera, typhus, and dysentery. Once the military looked at that eloquent graph, the modern army hospital system was inevitable. You and I are shown graphs every day. Some are honest; many are misleading….So you and I could use a Florence Nightingale today, as we drown in more undifferentiated data than anyone could’ve imagined during the Crimean War.” (Source: Leinhard, 1998-2002)

“Once you see Nightingale’s graph, the terrible picture is clear. The Russians were a minor enemy. The real enemies were cholera, typhus, and dysentery. Once the military looked at that eloquent graph, the modern army hospital system was inevitable. You and I are shown graphs every day. Some are honest; many are misleading….So you and I could use a Florence Nightingale today, as we drown in more undifferentiated data than anyone could’ve imagined during the Crimean War.” (Source: Leinhard, 1998-2002)

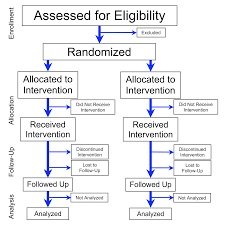

In a quasi experimental design

In a quasi experimental design